| |

Chinese Independent Cinema : origins, development and

present challenges

Le

cinéma indépendant chinois : origines, développement et

défis actuels

par Brigitte Duzan

|

“Chinese independent cinema” is an expression which

has been coined by the very directors most commonly

associated with the movement. It appears in the

title of a book which has marked their strongest

assertion of existence as a community, namely a

collection of interviews with ten directors

published in 2007 under the title “On the Edge :

Chinese Independent Cinema” (《中国独立电影:访谈录》)

(1).

By that

time, it was generally accepted as a common

reference for those filmmakers and applied to a

movement which had evolved from a chaotic

underground movement to a more disciplined one,

trying to negotiate with the authorities for a

recognized position within Chinese cinema. But it

had begun some eighteen years before.

It all

started in the aftermath of the Tian’anmen events of

June 1989, in a period of repression, of drastic

curtailment of |

|

On the Edge : Chinese

Independent Cinema |

the relative

freedom that had blossomed in the few years before. It

resulted in a breach in the monopolistic state system, but

it was not so much a conscious move towards artistic

freedom, still less a gesture of defiance ; it was rather a

personal initiative driven by circumstances. It then

developed because technical progress made it possible to

shoot a film on a shoe-string budget, without the need to

depend on a studio.

This is the

first signification of what is meant by Chinese independent

cinema : mainly underground filmmaking, breaking loose from

the state-sanction production system. Thence the first

questions which come to anybody’s mind : How did this

happen, and why ? And as in a criminal movie : who did it ?

Then how did it become a full-fledged independent movement ?

But a further

reflection inevitably leads to question the very concept of

independence : it does not exist in the absolute, but is

always defined as an absence of dependence on something or

somebody. The next step therefore leads to ask : can we

really speak of independent cinema ? Has it ever been

independent ? Is it a significant concept today ? And if

so, in which respect ?

I.

Independence : origins and development

Chinese

independent cinema developed at the same time in both

documentary and fiction, and actually blurred the two

concepts : independent cinema is also a stylistic story. The

chronology usually starts with one specific fiction film and

filmmaker, but we have to add the documentary counterpart to

have the whole picture, especially since the cross-breeding

happened from the very start.

1. Fiction

films : Zhang Yuan

|

Zhang

Yuan (张元),

who graduated from the Beijing Film Academy in June

1989, is generally credited with the first

independent film of the post-Tian’anmen period :

« Mama ». This is not exactly so, but it did signal

a movement to cut lose from the State studio system

to shoot films that could not otherwise have been

made. It is interesting to underline that Zhang

Yuan’s decision to shoot outside a studio was a

circumstantial move, and had originally no definite

pre-intention, just the desire to finish a film…

a)

« Mama »

« Mama »

(《妈妈》)

started as a project of the Children’s Film Studio ;

Zhang Yuan was still a student at the Beijing Film

Academy, but was supposed to be the film’s

cinematographer, his major at the Academy. The

script was called « The Sun Tree » (《太阳树》).

Zhang Yuan worked on |

|

Zhang Yuan |

the storyboard

with the scriptwriter Qin Yan (秦燕),

who was also to be the lead actor in the film. But, three

months later, the studio decided to cancel the whole project

which was not deemed profitable enough.

|

Dai Qing |

|

It was

then taken over by the August First Studio, this

time with another director, but Zhang Yuan again as

cinematographer. He was even sent scouting for

locations as far as Dunhuang. But the project was

again cancelled, after the Tian’anmen Square events,

mainly because the script was based on a short story

by Dai Qing (戴晴).

Originally an engineer working on guided missile

systems for the PLA, Dai Qing became an army writer,

then, in 1982, a columnist for the

|

Guangming Daily

(光明日报) ;

in 1989, she openly opposed the Three Gorges Dam Project,

and collected material on the subject which was later

published in a book. At the time of the Tian’anmen Square

protests,

Dai Qing joined other scholars, calling on the government to

curtail corruption and support democratic reform. When

students staged large protests that included a hunger

strike, Dai Qing made a passionate speech on Tian’anmen

Square, encouraging students to leave peacefully to avoid

bloodshed. She was one of those who warned the students

that, if they stayed, they could provoke a violent crackdown

that could seriously set back the process of reform. She was

not heeded, and the crackdown came on June 4. Dai Qing was

arrested on June 14, and stayed in prison until January

1990, but was still kept under surveillance until May.

|

Under

those circumstances, the film project was

understandably shelved. But Zhang Yuan had already

worked so much on it, he did not want to give it up.

The film focuses on a librarian struggling to raise

her mentally handicapped son in Beijing while, at

the same time, dealing with an absent and

unresponsive husband.

Zhang

Yuan had developed a deep and emotional

understanding of the subject, and had even

interviewed several mothers of handicapped children,

interviews which he later integrated

|

|

Dongdong and his

mother, in Mama |

into his film,

increasing its feeling of gritty reality.

He therefore

decided to go ahead, and revised the script with his wife,

the scriptwriter Ning Dai (宁岱),

and with

Wang Xiaoshuai (王小帅).

He shot the film in his apartment, mostly in black and

white, on a shoe-string budget of 100 000 yuans, financed

with funds collected from his family and his friends, plus

grants he had collected from small enterprises, touring the

country with a letter of recommendation of the National

Association of Handicapped Children.

In China,

the film

was deemed much too dark, and was banned as soon as it went

public, in 1990 ; on the contrary, it was feted abroad in

various film festivals and even won the Special Jury Prize

at the Nantes Three Continents Film Festival in 1991. On

that occasion, the president of the Jury referred to Zhang

Yuan as “the first Chinese independent director and

producer”, to the astonishment of Zhang Yuan who had had no

idea of the sort.

In fact, it was

not even exactly true.

« Mama »

had been formerly

declared and registered, under a licence number of the Xi’an

studio. Those license numbers were necessary to get approval

to buy film rolls. Four copies were then made of the film,

one was bought by Shenzhen local governement, two others by

the provincial administrations of Hubei and Jiangsu, and

the last one by the city of Shanghai which, at the time, had

the only arthouse cinema in China. Strictly speaking, it was

therefore not really independent.

b) « Beijing

bastards »

|

This

was not the case of Zhang Yuan’s second film : “Beijing

Bastards” (《北京杂种》),

in 1993. From the very start, the film’s credits

show no sign of either licence number or film

studio : this very silence proclaims it is « hors

système ».

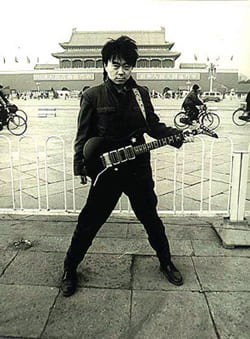

A bleak

picture of youth, played by rock musicians and

artists, blending reality and fiction,

it is an allegory of the situation in China after

Tian’anmen, meaning that the young Chinese

considered themselves as bastards of the regime. It

is a veiled denunciation of the repression which

followed June 4th, since the famous rock

musician Cui Jian (崔健),

who plays the main part, had his music played in the

square during the students’ protests, rock music at

the time being a sign and symbol of rebellion.

Zhang

Yuan has emphasized that the film also has its

message of hope : at the end, the crying new-born

baby is |

|

Beijing Bastards |

supposed to

symbolize the future renaissance of Beijing and its youth.

But it remains, on the whole, a grim, desolate and desperate

movie that no studio would have produced.

|

Cui Jian, symbol of

rebellion

beginning 1990’s |

|

It

could in fact be made thanks to a grant of the

Hubert Bals Fund of the Rotterdam Festival, and was

produced by three of the film’s main figures : Cui

Jian who plays the main part, but also wrote the

music and part of the script, Christopher Doyle who

was the cinematographer, and Hong Kong filmmaker Shu

Kei whom Zhang Yuan had met at the Nantes film

festival. However, for lack of money, postproduction

was suspended in 1992, and could be finished only

thanks to the help of the French ministry of

Culture.

So,

from this very start, independence was already quite

relative, since it entailed a dependence on foreign

sources of financing, technical backing and

promotion. This made the situation at home quite

difficult, turning into a kind of game of cat and

mouse.

What

made matters worse, was that Zhang Yuan “dared”

|

show his film

at the Locarno Film Festival, in spite of the Film Bureau

contrary advice ; they even threatened Marco Müller who was

at the time the director of the festival. The announcement

of the special mention garnered by “Beiing Bastards” was the

last straw. Zhang Yuan was officially condemned as

“spiritual polluter” and blacklisted.

The move was

rather drastic. Not only could he no longer make films in

China, other artists were also forbidden to work with him –

the ban extended to six other filmmakers ; studios were

forbidden to let them rent cameras or other equipment. At

the same time, the authorities promoted commercial and

‘harmless’ films, blockbusters (大片)

and New Year’s entertainment (贺岁片).

This further marginalized the young independent

filmmakers, but did not stop them. 1994-1996 is one of the

best periods for independent films.

Zhang Yuan went

on filming… but a documentary first : documentaries did not

have to be submitted to the censorship bureau, they enjoyed

relatively more freedom ; furthermore, it was adapted to the

very subjects the new filmmakers wanted to film, and indeed

it developed quickly in those years.

2.

Documentaries : Wu Wenguang

Here, again,

the general consensus is to point to a specific filmmaker

and film to mark the beginning of what has been called the

New Documentary movement. But the story does not

really start so abruptly. First, what appears as a sudden

shift of focus in subject and style comes from the preceding

period, from the “cultural fever” of the late 1980’s, and

the gradual consciousness that society was changing and

that, in the process, many people were left aside, on the

margins, and had to be accounted for, an awareness which

came along mainly because filmmakers identified with them.

But there was

no way for a filmmaker, still less than anybody else, to

express a personal view of what was happening, of what they

felt was happening. Documentaries in China since 1949 have

been a monopoly, in the hands of a central agency called the

Central Newsreel and Documentary Film Studio

(中央新闻记录电影制片厂),

created on the 7th of July 1953 as an agency

depending from the Party, as were the Xinhua Agency and

People’s daily. Documentaries had the sole purpose of

explaining history and serving official propaganda. They

were educational tools.

But they have

in fact a much longer history which needs to be quickly

recalled, to show that, when the new documentary movement

started at the turn of the 1980’s, it did not come entirely

out of the blue.

a) A long

history made short

|

The

Central Newsreel and Documentary Film Studio had its

origins in the Yan’an Film Group

(延安电影团),

founded

in 1938 under the leadership of the 8th

Route Army political department. But the first

documentary, called “Yan’an and the 8th

Route Army” (《延安与八路军》),

was

made by

Yuan Muzhi

(袁牧之),

who had just finished “Street Angels” (《马路天使》)

the year before. It was made in heroic conditions,

with a camera left by Joris Ivens, another one

bought in Hong Kong, and hardly enough film ;

post-production was made in Moscow in 1940, at the

outset of the war with Germany, so that the film was

lost.

But the

point, here, is that Yuan Muzhi himself was the

inheritor in the 1930’s of a documentary tradition

which can boast two leading forerunners : Sun

Mingjing and |

|

Yuan Muzhi |

Cheng Bugao. If

Sun Mingjing

(孙明经)

became part of the establishment after 1949, at the end of

the 1930’s he made a series of documentaries which can be

considered as independent : his series about the old

Tea-Horse Road, about the Ya’an salt-mines and about people

and sceneries in Xikang. But his purpose was mainly

educational.

|

Cheng Bugao |

|

This

was not the case of

Cheng Bugao

(程步高),

and he can truly be considered as a forerunner of an

independent documentary movement. He started his

career making documentaries in a small studio, the

Dalu studio (大陆影片公司),

which he created in the early 1920’s for the purpose

of showing what he was able to do and getting his

name known in order to gain entry into one of the

big studios of Shanghai. That is how and why he made

two documentaries : “Wu Peifu” (《吴佩孚》),

a portrait of a fascinating but ruthless commander

of the Zhili Clique, and “Luoyang Scenery”

(《洛阳风景》),

a forerunner of the Chinese “scenery films”.

Later

on, as he was working in the Mingxing studio, he

resumed shooting documentaries, at least on two

specific occasions : one in 1932, when the Japanese

launched their first assault on Shanghai, he went to

shoot “ The Battle of Shanghai” (《上海之战》).

But much more interesting is the |

film he made

one year later, the same year as his more famous « Spring

Silkworms » (《春蚕》).

The film is called “Wild Torrent” (《狂流》)

and was made on the basis of a documentary, but mixing

reality and fiction.

|

It all

started with a natural disaster in May 1931 : the

Yangzi flooded sixteen provinces. Cheng Bugao went

to film the disaster area around Wuhan with two

cameramen, and came back with a documentary showing

a shocking contrast between the poor victims

fighting to survive and the rich contemplating the

scene from afar. Back in Shanghai, he showed the

rushes to his friend Xia Yan (夏衍),

one of the leading scriptwriters of the Mingxing

film company with whom he was working on the script

of “Spring Silkworms” ; under the spell of these

images, Xia Yan imagined a story taking place in

that context, and focusing on the social conflict

between victims left fighting for themselves and

rich families going on with their life of leisure.

Cheng

Bugao then made the film, mixing footage from his

documentary with scenes of fiction, so that the

difference |

|

Xia Yan |

was blurred,

the main part being played by Hu Die (胡蝶).

The film had such an impact on the audience at its first

public screening, on the 5th of March 1933, that

it resulted in an immediate reaction of the Nationalist

government : studios suspected of leftist tendencies were

ransacked by squads of “Blue Shirts” and their films

blacklisted. It is generally considered as the true

beginning of left-wing cinema.

In this

respect, it must be underlined that the spirit that presided

over the emergence of this cinema as well as its later

development bears many similarities with the situation at

the beginning of Chinese independent cinema in the 1990’s.

When one considers the cinema produced in Shanghai in the

early 1930’s, the similarities are confounding. It has also

be noted by Zhang Zhen in her introduction to her book “The

Urban Generation” * :

“In modern

Chinese history, the 1930’s and 1990’s stand out as

strikingly parallel in terms of accelerated modernization

and urban transformation, aggressive industrial and

post-industrial capitalism, and an explosion of mass culture

with the accompanying issues of social fragmentation and

dislocation.”

A few lines

later, she adds this revealing comment :

“When asked

about the influence on him of the cinema of the 1930’s,

Zhang Yuan characterized it as “the most stylish and moving”

and “the most lively period” in Chinese film history.”

But chance was

the determining factor, like a spark igniting a pyre.

b) The New

Documentary movement of the 1990’s

It is not pure

coincidence that, in October 1993, the Central Newsreel and

Documentary Film Studio was formally placed under the

authority of CCTV. In fact, it was allotted such a

ridiculously small budget that it mainly subsists as manager

of the vast stock of documentaries it owns, which are

nowadays used by filmmakers shooting films on Chinese

history, and particularly the war. Official documentaries

are now made by and for television programs.

|

But, at

the same time, a new documentary movement emerged,

quite reminiscent of the 1930’s and in line with the

social preoccupations of the time, centred on the

lower and marginal classes of society, those bottom

(底层)

margins of the chaotic urban environment which the

fiction filmmakers were also focusing on.

It is

generally considered that the movement started in

the winter of 1991-92 : a big conference on

documentary filmmaking took place in Beijing at that

time, and was the opportunity to screen a number of

new works, mainly for television, but among the

films screened was the one by

Wu Wenguang (吴文光)

called “Bumming in Beijing : the last dreamers” (《流浪北京 :

最后的梦想者》),

which had also been screened at the 1991 Vancouver

festival. Wu Wenguang’s intention was to get away

from the newsreel style of Chinese

|

|

Wu Wenguang |

official

documentary as it had evolved since Yan’an times, and revert

to a cinematic style, at a time when the general

preoccupation was to fight against a return to ideological

rigidity in the aftermath of Tian’anmen.

|

Bumming in Beijing |

|

Wu

Wenguang had started his film at the beginning of

1989, focusing on five of his artist friends, all

illegal residents in Beijing who, in order to try

and fulfil their dreams, had refused a job in some

remote province after graduating from university. He

was trying to capture an authentic impression of the

dark reality of life in the post-Tian’anmen back

alleys of the capital. The film broke new ground in

its style as well as its subject : it was influenced

by the cinéma-vérité style used in a Japanese TV

serial famous at the time, and developed into a

personalized and subjective approach. It is shot in

long slow sequences, like reflecting on empty

spaces, with long moments of silence, recalling

classical painting where the void is the main

element. But these moments of silent reflection are

like the negative echo, the other face of the

Tian’anmen protests, the silence after the storm. It

is a rather gloomy reflection, without any positive

outcome. |

|

Wu

Wenguang was very close to the other filmmaker at

the start of the independent cinema movement, this

same Zhang Yuan who launched the break with

the studio system and whose third film was,

actually, a documentary of the same kind,

co-directed with another member of the new

documentary movement, Duan Jinchuan (段锦川):

“The Square” (《广场》).

It seems that the idea of the new documentary

movement was initiated at a private meeting in the

house Zhang Yuan had then in a hutong in Xidan

(which has since then been destroyed). But the term

itself appeared for the first time on the documents

presenting “The Square” at the 16th Hong

Kong International Film festival, in 1993.

Zhan

Yuan films ordinary, everyday life on the square :

children playing with kites, old people playing

frisbee, people |

|

Duan Jinchuan |

passing by,

bicycling, others visiting, everything is quiet, peaceful.

But then, there are the policemen and soldiers, revealing

the omnipresent control of the State. And at the end of the

film, salves of cannon are fired, for some visiting foreign

statesman, and suddenly there is a flash of anxiety, tension

flaring on everybody’s face…

The film was

made right when Zhang Yuan had been blacklisted and

forbidden to film in China. He did it pretending to be

working for CCTV. He captures every reaction, without

dialogues nor music.

Duan Jinchuan,

for his part, was influenced by Wu Wenguang whom he met in

1990 while he was shooting “The Last Dreamers”. Both of

them, in turn, were influenced by other documentary

filmmakers’ works they saw in 1993 at the Yamagata Film

festival, where Wu Wenguang was awarded the Ogawa Shinsuke

prize for his documentary “When I Was a Red Guard” (《我的红卫兵时代》).

They were particularly awed by Frederick Wiseman and Bob

Connolly.

|

Wang Xiaoshuai

(王小帅)

too was part of the early days of this new

documentary movement. He had been sent to the Fujian

studio, in 1988, but managed to find enough money,

about 10 000 $, to shoot his first film, in 1993 : a

fiction film, but focusing on the life of two young

painters who were playing their own part. In

English, it is called “The days”, but the Chinese

title (《冬春的日子》)

means ‘the days of Dong and Chun’. The man was in

fact the now famous painter Liu Xiaodong (刘小东),

who at the time led the same marginal life as Wu

Wenguang’s friends.

The

film was immediately put on the black list, but this

kind of subject became commonplace. It was still the

subject of the first full-length documentary made by

Huang Weikai (黃偉凱)

in 2005 : “Floating” (《飘》),

on the wanderings of a street musician. |

|

The Days |

In the second

half of 1995, however, the independent filmmakers turned

again to fiction. But in doing so, they incurred the wrath

of the authorities.

3. The turning

point of 1996

a) New

restrictions

|

Then,

in 1996, he made

« East Palace, West Palace »

(《东宫西宫》),

the first film in China overtly on the subject of

homosexuality, subtly using the theme as a symbol of

the opposition between official and underground,

between centre and margin, and reverting to the old

imagery and symbolism of Chinese traditional opera.

This was enough to have problems.

In

addition, however,

Zhang Yuan managed to get his

film out of China for post-production in France. In

1997, it was then part of the official selection of

the 50th Cannes film festival, section

“Un certain regard”, and was widely publicized.

When Zhang Yuan came back to China afterwards, he

was deprived of his passport and the Chinese

authorities had passed drastic measures to make sure

this unfortunate state of event would not happen

again in the future - which heralded a period of

tightened shooting conditions. |

|

East Palace, West

Palace |

The 1st

of July 1996, the SARFT (State Administration for Radio,

Film and Television) issued a new regulation in 64 points

which strictly forbade the making of any film outside the

state studios ; in addition, no film could be produced,

distributed or imported without prior agreement of the

censorship authorities. Of course, as many Chinese laws and

regulations, it is a masterpiece of ambiguity, ideal to

justify the interdiction of any film whatsoever : it starts

with six good reasons to ban a film (if it constitutes a

danger for the State, defames it, reveals State secrets,

encourages pornography, superstition or violence), but then

a seventh point adds that it can also be banned “for any

other content forbidden by the legislation.”

A double

movement immediately followed – the one towards continuing

independence, the other back to the studio system - but both

with dire consequences.

b)

Movement back to the studios

This new

1996 regulation started a movement back to the studio

system, since it was in theory now impossible to make a film

outside a studio. But it is also the beginning of very hard

times for those who decided to reintegrate the system : the

art of compromise became a must, a quite frustrating art of

compromise. Here again the cases of Zhang Yuan and

Wang Xiaoshuai are

emblematic.

1. Zhang

Yuan

|

In

1999, Zhang Yuan makes a film in the Xi’an studio

which marks his return to the State system ; it is

his first film to have been released in China :

“Seventeen years” (《过年回家》).

The story takes place in Tianjin ; a young girl who

has just spent seventeen years in prison for killing

her half sister is granted permission to go back to

her family for the New Year ; but, at the moment of

leaving, nobody comes to collect her. A young female

prison guard then offers to accompany her back home.

But, when they arrive, they discover the old house

has been torn down and her parents have moved

somewhere else…

It took

Zhang Yuan a whole year to get his script approved,

but he did, and he even got the authorization to

film within a prison, which actually was the main

reason why he so much wanted to have his film

approved. It was the first time a

|

|

Seventeen Years |

camera entered

a Chinese prison. The film was released in December 1999,

and it was a big success.

2. Wang

Xiaoshuai

The other

interesting example of early attempts to play by the rules

is that of

Wang Xiaoshuai, who was one

the first to decide to do so. But it was not such a success

story.

|

Way back in 1994, he had conceived a

project which was supported by

Tian

Zhuanzhuang (田壮壮).

It was originally called “The Vietnamese Girl”, but

the script was refused by the censorship bureau. It

took three years of negociating, arguing and

bickering, even the title had to be changed. Finally

the film was authorized, under the Chinese title

“The porter and the girl” (《扁担·姑娘》)

- translated

“So Close to

Paradise”. It was produced by Han Sanping and the

Beijing studio.

But

the finished product had hardly anything to do with

the initial project. It has kept something of the

original film noir atmosphere and style, with a

wonderful work on colours, watered blues slashed by

sudden outbursts of light and flashes of red, but it

is so diluted it has lost all significance. Censors

have changed the focus, from style to emotion, in a

very ordinary Chinese fashion, and the script itself

is at times incoherent, making it hard to follow the

story. |

|

So Close to Paradise |

What is

worse is that accepting the censors’ requirements did not

even help the film get a good distribution, since it was

still considered with suspicion, even hostility, by the

authorities, for its dark atmosphere and pessimistic vision

of urban reality. Production started in 1994, but it was not

distributed in China before autumn 1998, and still with

limited diffusion. It was shown in Cannes in May 1999, in

the section “Un certain regard”, and was granted the Tiger

award of best film at the 2000 Rotterdam film festival, but

it remains a film of compromise.

It had been

supported by Wang Xiaoshuai’s friends in the Beijing film

studio who had lost a lot of money with it. So Wang

Xiaoshuai then made a comedy, hoping they would thus recoup

at least part of their losses. But the film was shot in

nightmarish conditions, and resulted in still worse losses.

So, for his

next film, Wang Xiaoshuai did not bother to pass censorship,

with the result that the film,

“Beijing Bicycle” (《十七岁的单车》),

was banned, in 2001. He had gone full circle.

c) Continuing

independence from the studios

The

frustrating limitations of working within the system were

enough to convince many independent filmmakers to remain

independent, in spite of the difficulties. But, at that very

moment, fortunate circumstances made it easier to film

outside the studios.

The

so-called ‘digital revolution’ changed the rules of

the game. Not only was it now possible to have light

equipment, with the possibility of editing the film on a

personal computer, it was also perfectly adapted to the

mainly urban subjects filmed : it permitted a free and

personal style, a vivid rendering of day to day, ordinary

life close to the characters depicted. And it was cheap.

1.

Documentaries

|

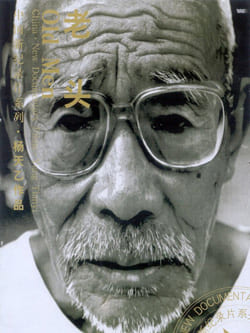

Two

documentaries made in 1999 can be considered as the

turning point of the digital era in China, which at

the time coincided with the development of

independent cinema : “Old Men” (《老头》)

by Yang Tianyi (杨天乙)

, and “Beijing Cotton Fluffing Artisan” (《北京弹匠》)

by Zhu Chuanming (朱传明).

Yang

Tianyi

is a typical case of this new generation of

filmmakers who emerged in the aftermath of 1996. She

was a dancer, then, in 1992, entered the PLA Art

Academy to become an actress, and actually played a

part in “Platform” (《站台》)

by Jia Zhangke. In her last year as a student in the

Academy, as she came back home, everyday, she saw a

group of old people who sat in front of the

apartment building where she lived ; she eventually

bought a small digital camera and filmed them for

two years, following their regular coming and going,

and registering their conversations.

|

|

Old men |

Zhu Chuanming’s

case is slightly different as he worked first in a

petrochemical factory at the end of his studies, before

being admitted into the Beijing Film Academy to study

photography. It is while he was wandering in Beijing,

looking for subjects for photos, that he met a young migrant

worker, who recycled the cotton of old cushions and quilts

in a derelict hut along a main road. After a while, he

decided to film him, using an ordinary family-type camcorder

to do it ; the image is not the best, but the film is quite

exceptional, with a rare depth of

human and emotional feelings.

|

Jiang Hu |

|

DV was also instrumental in enabling older

filmmakers to renew their style, like Wu Wenguang

using a Betacam SP camera to make “Jiang Hu, a Life

on the Road” (《江湖》),

that same year 1999. But the two previous cases are

a kind of model for everything that was to develop

in the following years in the field of independent

documentary, leading to such masterpieces as

Wang Bing (王兵)’s

“West of the Tracks” (《铁西区》)

in 2003,

Zhao Liang (赵亮)’s

“Petition” (《上访》)

five years later, or

Xu Xin (徐辛)’s

“Karamay” (《克拉玛依》)

in 2010 : all |

works conceived and filmed over long periods of time, in a

symbiotic relationship between the filmmaker and his

subject.

However, this

development was not restricted to documentary ; or rather

this documentary style extended to fiction, and, at the same

time, the whole movement took a different spirit, another

face and renewed energy. It is often considered as a

second phase of the independent film movement.

2. Fiction

The

initiator of this change in the late 1990’s was of course

Jia Zhangke (贾樟柯)

whose “Xiao Wu” (《小武》)

in 1997 and “Platform” (《站台》)

in 2000 launched this new phase. Jia Zhangke and his friends

of the Beijing Film Academy Young Experimental Workshop were

born in the early 1970’s, raised in the era of reform, had a

strong distaste for the kind of filmmaking taught at the

Academy and a burning desire to make their own voices heard.

The big

difference was that Jia Zhangke came from an ordinary

lower-middle family, in a small town in Shanxi. He had to do

odd jobs to earn a living as a student, painting

advertisement billboards and putting up shop signs in

Taiyuan, Shanxi capital. When at the Beijing Film Academy,

he supported himself by writing TV episodes as a ghost

writer. He therefore wanted to reclaim cinema as means of

communication for the ordinary citizen, the one caught in

the midst of urbanization and economic turmoil. Beijing

Bastards were angry artists, Xiao Wu is a poor pickpocket in

the backwater of modernization.

Jia Zhangke

eagerly took advantage of the digital revolution, which was

also a cinematic democratization. He started with his short

documentary “In Public” (《公共场所》),

in 2001, because it was made for the festival of Jeonju in

South Korea, which makes it one of its requirements. But it

influenced the making of the film, giving him a lot of

freedom of movement. Then, partly since his next film,

“Unknown Pleasures” (《任逍遥》),

had serious budgetary problems, he also shot it in digital,

very quickly, in nineteen days.

But this

film marks the high tide of the digital movement, Jia

Zhangke explained he found the technique has limitations and

he had to cut a number of scenes because the quality was not

good enough. It is also the last film he made outside the

studio system. 2002 is also a turning point.

4. The

other turning point of 2002

The

restrictions and controls exerted on cinema after 1996 had

had dire consequences. The number of films made annually

fell from a yearly average of approximately 150 in the

mid-1990’s to 88 in 1997 and even 82 in 1998. Still worse,

of the 88 films produced in 1997, only 44 obtained approval

for release from the censorship bureau. Audience numbers

plummeted. But Titanic made 4 million US$ in Beijing movie

theatres alone in 1997.

a)

Restructuring and drive for profit

The threat

represented by imported films, mainly American, coupled with

the poor results of domestic films, were enough to

precipitate a dramatic reconstruction of the State-owned

film industry. Starting in 1999, some State-owned studios

began to be restructured along the lines of joint-venture

companies with private investments, or incorporated into

large entertainment-related enterprises. The movement

started with the Beijing Film Studio ; the model was in turn

borrowed by the Shanghai film studio, then those of

Changchun and Xi’an. Then, as the three sectors of

production, distribution and exhibition were opened to

private companies, local and international investors got

involved in the moviemaking industry. Furthermore, in 2003,

limitations on co-production were lifted ; non-State

production companies could apply for production licenses.

As a result,

the involvement of foreign capital in all sectors of the

film industry undermined the very nature of Chinese cinema.

Long considered a pedagogical tool used to support Party

policy, it had increasingly to respond to the demands of

domestic and foreign investors for profits. As a result, in

the early 2000’s, profit making, and therefore

commercialization, became a major preoccupation of the

Chinese film industry.

b) Relaxation

of censorship

This

preoccupation induced a relaxation of censorship procedures.

In September 2003, the SARFT issued new regulations for

script approval : a draft script had to be approved prior to

shooting, but, after the film was completed, it could be

submitted to local or provincial censorship committees. Out

of 214 films completed in 2004, only one HK movie was

rejected, because of its depiction of violence, and in 2005,

251 films passed censorship. Most of the investment in these

films were from non-State companies.

c) Resurfacing

of many independent filmmakers

As a result of

this loosened censorship control, announced in a solemn

meeting in December 2003, many independent filmmakers had

their films approved for release. Jia Zhangke was one of

them. He has repeatedly said in interviews that the reason

for his surfacing from the underground was only the relaxed

environment of censorship :

“Originally…

the censorship apparatus was, to a large degree, restricting

our freedom of choice. But now, it looks like we’ll have the

chance to express ourselves freely, and that’s why I’m

willing to give it a try.” (2)

He had prepared

himself for lengthy requests for revisions, but it was not

even the case : he had to review the language used in a few

lines of dialogue, ant that was it.

Others also

joined mainstream cinema at the same time and for the same

reason.

Wang Xiaoshuai had the ban

on

“Beijing Bicycle” (《十七岁的单车》)

lifted ; then his 2005 film,

“Shanghai Dreams” (《青红》),

was approved by the censors, and even submitted to the

Cannes film festival as China’s official submission. Similar

cases occurred for Lou Ye (娄烨)

-

“Purple Butterfly” (《紫蝴蝶》)

was

allowed to show in China, which might explain the flaws and

discrepancies in the script, but he has since then reverted

to a defiant underground, while others like Jiang Wen (姜文)

have taken the commercial mainstream option.

II.

Double Dependence : Present Challenges

The problem

nowadays is that this relaxed atmosphere has not survived

the Olympic Games, and the so-called independent cinema has

now fallen into a double dependency : worst censorship ever

and obsession for the market. In other words, economic

constraints are now added to political or ideological

restrictions, the worst of situations.

But independent

cinema still survives at the margins, and remains, in spite

of everything, a creative sector full of drive and dynamism.

1. The

challenges

a) The

challenge of censors

Nowadays,

censorship has become obnoxious even for the best mainstream

filmmakers. Two recent anecdotes reveal the underlying

tension among the profession.

|

1. In

August 2011, a theatre play was a tremendous hit in

Beijing. It was a comedy, called “The sorrows of

comedy” (《喜剧的忧伤》),

and the main part was played by the popular actor

Chen Daoming (陈道明),

but this does not entirely explain the reason for

its incredible success. It is in fact a satire of

the absurdity of censorship now prevailing in China.

The

main character is a writer of comedies who wants to

have his latest script approved. The play takes

place in 1940, |

|

Chen Daoming en

censeur borgne

dans « The Sorrows of

Comedy » |

and the censor

is a general who recently came back from the front, where he

lost an eye. He begins saying that people don’t want to

laugh in time of war, then, in the following week, starts a

thorough analysis of the script, asking for the most

delirious and hilarious revisions.

This is the

funny part, but the sad one came later : after the premiere,

there was a cocktail party attended by the best and the

brightest of Chinese theatre and cinema. Among the

celebrities attending was

Feng Xiaogang : he was reported to have been so

shocked by the play that his hands were shaking and he

dropped his glass which crashed on the floor. His wife, the

actress Xu Fan (徐帆),

collapsed on her knees to collect the pieces and burst down

in tears. She later wrote on her micro-blog : “The comedy

has turned into a tragedy.”

2. Then, in late August, the same

Feng Xiaogang burst out during a formal address

at an official conference about the so-called “Cultural

Reform”. His words were quoted in an article of the People’s

Daily, at the end of the month :

“The

pressure of censorship on filmmakers and creators has been

reinforced. The

SARFT makes

dubious interpretations of everything, and passes judgments

on questions of principle. The required revisions have

become ridiculous…. This stupid system is hampering

cinematographic creation and thus damaging it.”

He added :

“A film is

defined as “positive” or “negative”, this is the only

criterion of judgment used by the censors, but, at the same

time, artists are required to create works able to survive

in the future, as if the great classical works of the past

could be judged according to their being “positive” or

“negative”. The result is that everybody now prefers to

remain on the safe side, and avoid contemporary subjects

which might be deemed “negative”.” (3)

If this is true

of somebody like

Feng Xiaogang, one can

easily imagine what it can be for young filmmakers trying to

create something new and original.

But the most

tragic is that filmmakers are now much more pressured by the

drive for commercialization, the obsession with the market.

Having a film approved is not the end of the story. And

that’s where independence becomes much of an illusion.

b) The pressure

of the market

The drive for

the market is not in itself something new ; it dates back to

the 1980’s, at a time when the authorities tried to

reconstruct a system which had become obsolete and

financially bankrupt. Subsidies were curbed, and studios

given increased autonomy. At the same time, there was a

rediscovery of the audience, its tastes and aspirations,

better known thanks to opinion and popularity polls, in

particular those of the journal “Popular Cinema” (大众电影).

This led to a

change in the tripartite balance of power defined by Paul

Clark, between the Party, the filmmakers and the public (4),

and had positive results : the policy of “opening up” in the

field of cinema also meant stylistic experimentation, a

complete renewal of styles and themes.

But the

autonomy granted to the studios also gradually led to more

dependence on financial results, and therefore on the box

office, to be able to optimize returns on investments. It

became an obsession after the financial and restructuring

reforms at the beginning of the millennium.

In the early

2000’s, the film authorities formally acknowledged cinema as

an industry which, from then on, had to operate first and

foremost on the basis of the market and aim at

profit-making. As is often the case, the change appears in

the very wording of the official documents : they had

previously referred to cinema as a “service”, an undertaking

with serious political and pedagogical functions (shiyè

事业);

now, the new documents issued by the SARFT began using the

word “industry” (chǎnyè

产业).

The official

discourse then continuously emphasized the need to

industrialize Chinese cinema especially in order to make it

competitive on the international markets, a

new policy that

was developed in the wake of the 16th National

Congress (5). In that context, it was of course the

Hollywood model which was in everybody’s minds, for State as

well as private film productions. But the commercialization

of cinema also had its domestic component, that is the

targeting of domestic audiences to make them into a

profitable market.

The latest

development was brought about by “Avatar” when it was

released on the mainland in January 2010. Titanic had been a

shock, Avatar was almost a trauma. The Chinese film

authorities now have only one goal : master the 3D technique

and beat the Americans.

c) The

marginalization of small budget and art films

The result is a

resolute expansion of chains of big movie theatres catering

to a mainly urban, white-collar and trendy audience which

considers cinema as a fashionable entertainment. It is also

an expensive one, and more and more so as movie theatres are

developed as a form of very lucrative investment.

Nowadays, less

than 20 % of films made and approved are released in

mainland China, and about half can boast to have a good

distribution, so that independence has become more of an

illusion, and a marginal question anyway. Mainstream or

independent, filmmakers are all in the same situation. If

they don’t produce films promising to be big hits, they have

no chance of being released. Not long ago, it was censorship

their worst problem, and the reason for their choice of

independence, with the consequence that they were dependent

on international festival circuits for international

recognition. But they were disconnected from the audience in

China.

Today, market

forces are much more insidious than censorship, but the

result is still the same : independent filmmakers are

disconnected from their domestic audience, and the solution

does not seem easy to fathom. They depend on small venues,

film bars, minjian film clubs, university backyards,

but more and more on domestic film festivals. Those are a

new interesting phenomenon which is tolerated by the

authorities provided they do not make too much

advertisement, and keep a low profile. One of the latest

creations, the

Beijing

First Film Festival, founded and animated

by Wen Wu (文武),

seems to

be gathering momentum, and gradually building an audience ;

it has even started a cooperation with the French festival

Angers Premiers Plans.

Another

promising development could be the internet, with the

diffusion of VOD on dedicated sites like tudou or

youku. But it is all very fragile, since dependent on

the vagaries of politics and on the bigger problem of the

definition of a public space.

However, the

spirit of independence still lingers, and, while mainstream

cinema hardly departs from historical blockbusters or

comedies, in a cautious move to limit risks and optimize BO

returns, the few remaining so-called independent filmmakers

are creating interesting new forms and styles.

2. A continuous

creative drive

Some filmmakers

have opted for an image of artiste maudit, defiantly

pursuing works produced abroad and tailored for

international audiences, but totally cut from the mainland.

This is, for instance, the case of Lou Ye, but his talent

seems to be waning.

More

interesting is the multifaceted stylistic and aesthetic

research pursued by various filmmakers in China, engaged in

a rhizome-like diversification of styles.

a) Lines of

flight

Documentaries

certainly are the most numerous works representative of the

Chinese independent movement. Many documentary filmmakers

continue their socio-political critique (Du

Haibin,

Wang Bing,

Xu Xin…)

: those are documentaries treated like works of fiction,

with a strong narrative line emphasized through careful

construction and editing.

|

But

there is also a strong trend towards focussing on

the private, intimate and day to day life (Liu

Jiayin (刘伽茵)’s

“Oxhide 1/II”

《牛皮贰I/II》),

or even spiritual experience (Ma Li’s

“Mirror of Emptiness”

《无镜》).

There are so many documentaries being made right now

on all aspects of Chinese life, society and even

scenery that it will constitute a formidable archive

for the future, if they are well preserved, which is

a point to keep in mind.

The

general picture is one of swarming talents of

various origins, especially, now, on the margins.

There is a whole array of photographs and painters

whose works have a distinct aesthetic quality, and a

cross-breeding with the artistic scene. They are

part of a strong movement of experimental video,

with diversifications in the field of animation.

|

|

Liu Jiayin |

b) Lines of convergence

It seems there are thus innumerable lines of flight, an

incredible creative richness which barely surfaces but is

the most pregnant of Chinese cinema today, but which also

hides lines of convergence since there is a kind of group

phenomenon, around a school or around a person.

|

For instance, the Central Academy of Drama, in

Beijing (中央戏剧学院),

may appear as an alternative to the Beijing Film

Academy. From there comes a group of original

filmmakers like

Cai Shangcun (蔡尚君),

Diao Yinan (刁亦男)

or

Liu Fendou (刘奋斗),

who worked for a while together, at the end of the

1990’s, as scriptwriters for

Zhang Yang (张扬)

and Shi Runjiu (施润玖)

; Liu Fendou then started his own production company

and produced “Spring Subway” (《开往春天的地铁》)

by Zhang Yibai (张一白)

en 2002. It was then the best years for independent

cinema.

Private

groups have also emerged over time, many of them

created by the artists themselves. One example is

Zhang Xianmin (张献民)

and his Beijing Indie Workshop (影弟工作室)

founded in 2005 to promote Chinese

independent cinema and which has lately produced

“Old

Dog” (《老狗》),

the last film |

|

Zhang Xianming |

by

Pema Tseden

(万玛才旦).

Zhang Xianming is also the founding father of the Chinese

Independent Film Festival (CIFF) which is nowadays the most

important and influential venue for independent filmmakers.

This is

certainly one of the strengths of the movement : filmmakers

are not isolated, and they have a common sense of mission,

as Ling Zifeng (凌子风)

‘s son Ling Fei said in 2009 :

“At the

beginning, underground or independent films claimed an

engagement, a personal language. The filmmaker decided to

choose a subject the official cinema would never have

considered. So, there have been good films, but there have

also been films whose only specificity was in their subject,

irrespective of the way it was treated. Today, … if a

filmmaker decides to stay independent, it is because he

wants to concentrate on the artistic quality of his film,

and work independently of market trends.” (6)

But, in spite

of this creative impetus, there are signs of discouragement,

a perceptible mood of disillusionment which may be the most

worrying today. At their best, those filmmakers keep the

hope of being eventually able to work within the system and

having their films released domestically. But it seems to be

a long road to get there.

Conclusion :

2012, beyond independence, or independence on the margins…

The very idea

of independent cinema has been from the very start fraught

with illusions. Nowadays, independence in the realm of

filmmaking has lost much of the relevance it might have had

at one point in time. But since there is still a spirit of

independence as a creative force pushing forward unabated,

in this sense there is still an independent cinema in China.

Its main problem is now to get known, inside China.

The prevailing

model, in this respect, is Jia Zhangke. On can argue that he

is

trying to bridge the gap between independent and mainstream

cinema, trying to bring up a new narrative, new aesthetics

to the Chinese mainstream cinema. He is defining an

alternative way, and, in this sense, he may represent the

best hope for independent filmmakers by the way he manages

to have his voice heard in official circles, but without

compromising on his aesthetic principles, intent on

maintaining a relatively high freedom of artistic creation.

But he

has been rather absent lately and we are still waiting for

his next film, “The Age of Tattoo”, which has been in the

making for quite a while now.

However, even

in his case, the fundamental point remains the access to the

audience, and the screening opportunities. Jia Zhangke’s own

experience shows that even an official release is not the

end of the problem. When “The World” (《世界》)

was released, it hardly made 100 000 euros, and soon

disappeared from the few screens where it had been shown.

When “Still Life” (《三峡好人》)

was released, on the 14th of December 2006, it

was the same day as

Zhang Yimou’s “Curse of the

Golden Flower” (《满城尽带黄金甲》).

“Still Life” had just been awarded the Golden Lion in

Venice, but it was released at odd hours, at 9 in the

morning or 1 in the afternoon in many places, how can a film

compete against an official blockbuster in such conditions,

without even speaking of the difference in promotion budgets

?

In addition,

tickets price in China are today much too expensive :

cinemagoers prefer to go and see the big dapian which

makes the headlines or the latest comedy hit which seem much

more rewarding in view of the money spent. If cinema has

become an industry, for the audience, it has become pure,

but expensive, entertainment.

Raising public

awareness, forming the tastes of the public are nowadays the

most difficult challenges for Chinese independent cinema.

This was clearly indicated in a recent initiative made at

the last meeting of the Association of Chinese filmmakers,

in 2011. The Association had created prices in 2005 which

have been granted only twice since then. It seems they now

want to actively promote young filmmakers and small budget

films ; interestingly, there is no mention of independent

cinema per se, which is revealing, but the initiative is led

by respected figures like

Tian Zhuangzhuang (田壮壮)

and

Xie

Fei (谢飞).

The latter announced that their main objective was to

negotiate with movie managers to give small budget films

more visibility, one of the points to discuss being a

decrease in tickets prices in specific cases (7).

But the main

problem arises from policies which are insisting on

considering cinema as an industry, with the only purpose of

making profits. It is indeed nowadays restricted neither to

China nor to cinema, but it has taken unique proportions in

China. Since 2003, the SARFT has been collecting 5% of box

office revenues, to finance a fund dedicated to the

development of the “film industry”. Even big production

companies are affected ; Huayi, for instance, had to pay

SARFT half of its 2011 profits. And this goes to finance

such films as Wuxia or the latest 3D blockbusters.

We are

witnessing a return to quantitative practices that are

redolent of past times, we also feel a terrible sense of

urgency, in official circles, of catching up, akin in spirit

to the Great Leap Forward, with cinema replacing steel, and

Hollywood Britain. But the combination of tightened controls

and the urge to “industrialize”, make profit and compete on

international markets has resulted in 2012 in a dearth of

good Chinese films. The exceptional growth figures of the

mainland box office are due for the main part to the

American blockbusters’ continued success.

In this dire

situation, independent cinema is fighting for survival. A

double movement is taking shape : many independent fiction

filmmakers are going back to the mainstream in the hope of

getting more visibility in their country, and to try and get

some financial return on their work ; the big names have

left the boat. At the same time, there is a frenzy of

documentary filmmaking, mainly because there are so many

attractive subjects and shooting with light digital cameras

is easy and cheap. The result is not necessarily

satisfactory in qualitative terms.

There remains a

small number of very good documentary filmmakers who will

continue to work independently because they need to retain

their freedom of expression. An interesting development now

seems to be the

experimental cinema

which has appeared on the margins, but with a different

model altogether : initially backed by the big institutions

like the Beijing Film Academy and the

Central Academy of Drama, it is now evolving as an artistic

movement which might well provide in the years to come the

best and the brightest at the brink of independent cinema.

Notes

(1) The

interviews were edited by Ouyang Jianghe (欧阳江河),

a poet and

prominent critic of music, art, and literature ; as he was a

key figure of the literary magazine Jintian,

the interviews were

published at the same time in a special issue of the

magazine and in Hong Kong by

Oxford University Press, in 2007. This is a common

reference.

(2) Valerie

Jaffee, « An interview with Jia Zhangke », Senses of Cinema,

June 2004.

(3) Voir :

http://www.chinesemovies.com.fr/actualites_2.htm

(4) Paul Clark,

Chinese Cinema : Culture and Politics since 1949, 2-3.

(5)

In January

2003, the vice-director of the Film Bureau of the SARFT made

a speech at the National Conference of Film Production,

where she proposed guidelines for 2003. Her speech was

entitled : “For a full implementation of the spirit of the

16th National Congress to promote and foster the

reform, development and renovation of the film industry” (全面贯彻十六大精神加快推进电影产业的改革发展创新)

:

http://www.law-lib.com/fzdt/newshtml/22/20051111212001.htm

(6) Interview by

Luisa Prudentino, Monde Chinois, Regards sur les cinémas

chinois, n° 17, p. 82.

(7) Voir

:

http://www.chinesemovies.com.fr/actualites_35.htm

Selected

bibliography

- Berry, Chris.

Postsocialist Cinema in Post-Mao China : the Cultural

Revolution after the Cultural Revolution, Routledge, 2004.

- Berry,

Michael. Speaking in Images : Interviews with Contemporary

Chinese Filmmakers, Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Clark, Paul.

Chinese Cinema : Culture and Politics since 1949, Cambridge

University Press, 1987.

- McGrath,

Jason. Postsocialist Modernity : Chinese Cinema, Literature

and Criticism in the Market Age, Stanford University Press,

2008.

-

Pickowicz,

Paul/Zhang, Yingjin (eds). From Underground to Independent :

Alternative Film Culture in Contemporary China, Lanham,

Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

- Zhang, Rui.

The Cinema of Feng Xiaogang : Commercialization and

Censorship in Chinese Cinema after 1989, Hong Kong

University Press, 2008.

- Zhang, Zhen (ed).

The Urban Generation : Chinese Cinema and Society at the

Turn of the 21st Century, Duke University Press,

2007.

Monde chinois,

Regards sur le cinéma chinois, Choiseul Editions, n° 17,

printemps 2009.

China

Perspectives, Independent Chinese Cinema : Filming in the

“Space of the People”, n° 2010/1

SARFT official

website :

http://www.sarft.gov.cn/

|

|